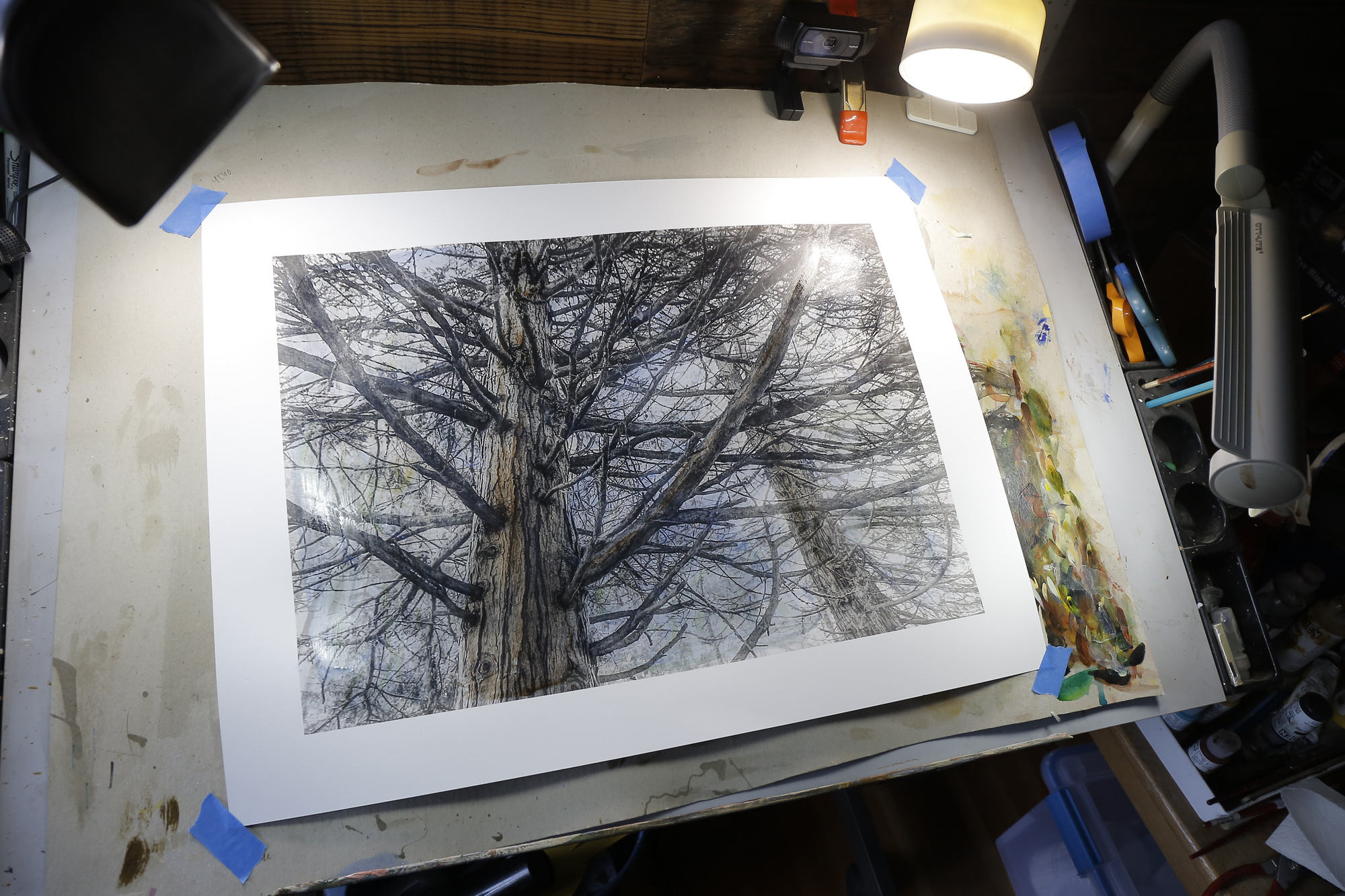

Here’s the black and white photo I took a few days ago in the woods:

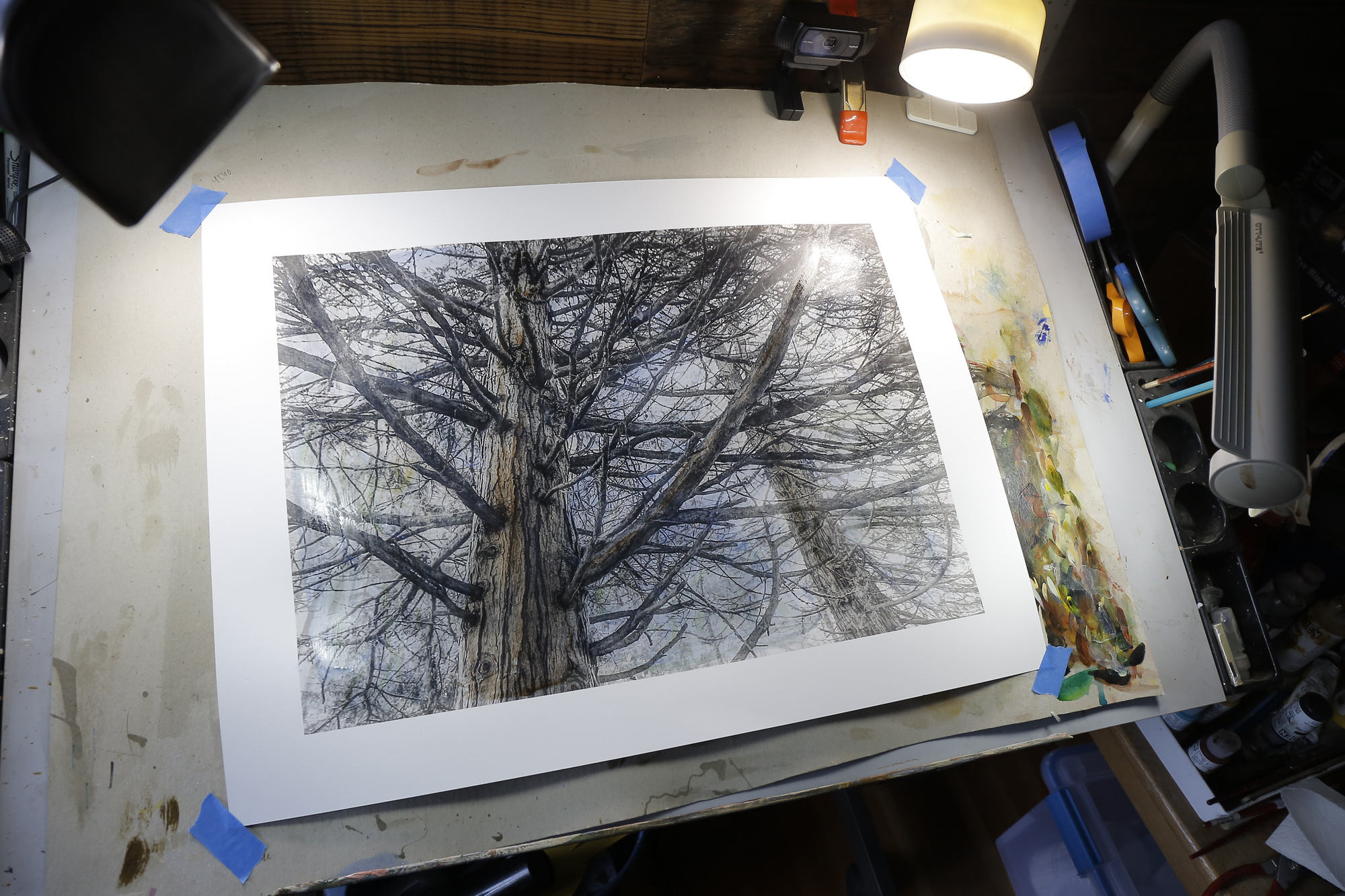

Here it is printed out and beginning to be colored with light washes of acrylic:

Hand colored photography from the Pacific Northwest

Here’s the black and white photo I took a few days ago in the woods:

Here it is printed out and beginning to be colored with light washes of acrylic:

Here’s an early look at a large (24-by-72-inch) hand colored print I’m making. The image of is a Great-horned owl that Noah and I encountered at Fields Oasis during our recent eastern Oregon adventure. The bird sat remarkably calmly as we approached around the rim of the small pond. Only when we got close could we see that the owl was hanging on to a rabbit it had caught, which explains why it wasn’t quick to flush.

Here’s another view of the owl, with a clearer look at lunch:

Both photos shot with the 36-Mp Pentax K-1, which gives enough detail to print a single image really big. So I thought I’d crop it down to a wide pano view, as you can see, and try a large black and white print to color. It came out with startling detail, including the interesting texture in the bright yellow iris of the owl’s eye.

This is a test print on cheap paper (it might be shelving paper, I can’t remember where it came from). Which is good, as the printer, which needs cleaning, threw a couple ink splatters. Fortunately they missed the owl, so I can fix them in the coloring process.

I’ve only just begun the coloring, with a couple quick layers of acrylic medium and a wash of ultramarine blue and some olive green on the out of focus background.

I’ve been on kind of a tear lately with photos from the woods. Our local forest, neighborhood clearcuts and all, makes a lovely subject for landscape photography, and I’m deeply enjoying making black and white images to take back to the studio and color.

As you can probably make out, I’ve been loading up the brush with more paint than usual, stretching the boundary of traditional hand coloring into something more approaching a painting on top of a photo. The photograph is definitely still there and still vital to the image, but I’m less shy about coloring over areas with abandon.

Here’s a look at that one on the right. Don’t mind the glare — I shot it on the ground outside, which means I’ll soon be re-shooting it a little more carefully:

Lots of paint piled up on the foreground ferns and other undergrowth. I’m not quite inventing things, just simplifying areas of color, and reinforcing shadows and highlights to give that area more structure.

If you mess around with digital photography, you’ve probably run into the acronym HDR. It stands for High Dynamic Range photography, and it refers to a techie method of merging bracketed exposures either in-camera or in post-processing software to extend the still rather limited dynamic range of digital sensors.

In plainer English, that means using, say, three exposures of the same picture to solve the wedding photographer’s problem: The bride’s dress is so white and the groom’s tux is so black that any single photo has got either blown-out whites or blocked-up blacks, or both. Merge one shot exposed for the bride and one exposed for the groom and you get the best of both.

HDR, though, is one of those things in which a little goes a long ways. Get it right and your photo looks like an artist’s painting. Get it wrong and it looks like something by Dali.

So I hadn’t tried it very much. Then I got a new Pentax KP last winter and was putting the excellent little camera through its paces, trying out every bell and whistle, and in the process tried out all five levels of in-camera HDR in black and white. Converting to BW gets rid of the lurid color associated with bad HDR photos.

The KP has this new HDR setting — simply marked “ADV” in the menus — that produces very compelling shots. They can look a lot like Tri-X souped in Rodinal, my favorite way to make prints to be hand-colored back in darkroom days, or even like fine art etchings.

That opened a new door for me. For the past three months I’ve been shooting everything in sight with the HDR process and making 18×24 prints to hand color. Still sorting this out, but the images are very compelling, and I’ve set up one of the User settings so I can set up HDR ADV in BW (how’s that for alphabet stew?) with one quick click of the dial.

Many more of these to come as I sort the process out.

Near Medicine Bow Peak

Every day, for the last three weeks, I’ve gotten up at dawn, eaten a quick breakfast, packed a small lunch, and headed out for eight to ten miles of hiking and photographing in the high sagebrush country of southern Wyoming. Then I come back, settle in to a private studio for the afternoon, and work until dinner on hand-coloring photos, painting them at an easel for the first time in my life instead of on a drafting table.

All this time I’ve been holed up at a luxury dude ranch in southern Wyoming with five other artists – all more accomplished than I, by far – at the posh Brush Creek Foundation for the Arts.

Part of Brush Creek Ranch, a 15,000-acre, $1,000-$1,500 a night resort that caters to some fraction of the one percent, the art foundation has been in existence for five years. The ranch is where Girls star Allison Williams was married last year to much notice in the celebrity press.

Like other arts residencies around the country and the world, Brush Creek Foundation offers a quiet place to live and work, in extraordinary surroundings, for perhaps 50 artists each year. For free. Did I say for free? Artists and art lovers tend to complain about a lack of support for the arts in the U.S. Well, this is support.

At work in my studio

When I arrived three weeks ago, I was picked up in Laramie – the closest commercial airport – and shuttled some 70 miles across southern Wyoming’s mountain and sagebrush country to my own little piece of Paradise: a small hotel style bedroom in a log building next to a second log building where I’ve got my private art studio, complete with high ceilings, a sink, a big wooden easel, desk, tables and basic supplies. And a great view of the rimrock outside.

I’ve never worked in a studio this spacious or elegant. Best of all, like all four visual art studios here, it comes with a Barcalounger, perfect for afternoon or evening naps and other deep inspired contemplation.

The only question I’ve got is, why have I never done this kind of thing before?

The other five artists here with me for the month are all easterners, oddly enough: Three New Yorkers, a Bostonian and a French Canadian.

New York performance artist Pat Oleszko on Open Studios day

Among us we are two photographers, two orchestral composers, a novelist and a performance artist who was once arrested in Rome for impersonating the Pope (as part of an art project, natch).

Four of us are in our 60s. Two are, ahem, younger. We get along amazingly well, considering we eat every dinner and many lunches together, and we see few other people day to day. The other artists tell stories about residencies wrecked by the occasional misfit. None of that has happened here. It’s a serious, good-humored group of actual adults. We’ve gotten together once to watch a presidential debate, and a few of us took a high-altitude hike near Medicine Bow Peak the other day. One resident, photographer and ceramicist Warren Mather, rented a car for the month, and has been generous with rides to town.

The weather has been spectacular. We got four inches of snow one day early on, but it all melted off in a couple more days, leaving us to enjoy sunny warm afternoons and cool evenings, sometimes spent around a fire pit well stocked with cut and split logs.

But mostly we work. Brush Creek offers what is called a “no expectations” residency, which means just that. No obligation on our part to do anything in particular at all. You can work, you can hike, you can take naps. You can present your work to the other artists (which we have all done) or not. No one judges.

Dinner

And you can just breathe the clean Wyoming air each morning and think, “What did I ever do to deserve this?”

The biggest artistic challenge I’ve faced is this: Since I decided to fly here, rather than drive 1,100 miles and back in uncertain weather, I don’t have my computer printer. So each day I shoot and edit photos, but can’t print them; instead I work on a stack of old black and white photographs I shipped to myself ahead of time via UPS. So I’m photographing Wyoming and painting Oregon each day. I’ll live, somehow.

No one seems to take days off. What would be the point?

Dinners and lunches have been catered by a Peruvian chef named Monika, whose husband Alejandro also works in the main lodge kitchen. Our meals have been opulent, night after night, almost to a fault. Monika and Alejandro finished their contract for the season the other night, so we celebrated with a full-on prime rib dinner with the works, leaving everyone stunned and satiated.

Pre-dinner cocktail hour by the firepit

The first resident to present his work to us was Jerome Kitzke, a New York composer who has performed all over the world. Tall, rangy and gray haired, with a long pony tail, he spends his days holed up in a cabin here called The Schoolhouse, which I guess used to be one; now it’s restored, looks a bit like a church inside, and sports one of the best 9-foot Steinway grand pianos I’ve heard played. (The other music studio has a Bösendorfer.)

One evening early on, Jerome invited us to the The Schoolhouse to hear him play a piano setting he wrote perhaps 15 years ago to Allen Ginsberg’s 1953 poem “The Green Automobile.” The poem is perfect for here, about an imagined road trip taken from New York to the West by Ginsberg to see Neal Cassady.

With a week to go before returning to Oregon, I find myself picking up the pace of photography, painting and just plain thinking. It’s hard in real life to find time like this to work on anything, and I don’t plan to lose a moment.

An abandoned cabin up a sagebrush draw on the ranch